Author: Antonia Pieper

When you think of the Netherlands, your first thought may go to images of tulips and beautiful canals, the flavors of smoked herring and mouthwatering blocks of gouda, or the excessive number of bikes. You might think of Amsterdam, of surprisingly proficient English-speakers, or perhaps even of the infamous red-light districts. For many people however, the European country has become almost synonymous with drug use and coffeeshops. In fact, recent figures suggest that around 22 percent of tourists between the ages of 18 and 35 visiting Amsterdam do so exclusively to spend time at coffeeshops (Sleutjes and Bosveld 2019).

Drug Policy in the Netherlands

Why have the Netherlands become a hub for recreational drug tourism in the first place? The answer to this particular question lies in the unique nature of Dutch drug policy.

Like in many other countries, Dutch drug policy generally follows four major goals: (1) to prevent drug use and treat and rehabilitate drug users, (2) to reduce harm to users, (3) to diminish public nuisance caused by drug users, and (4) to combat the production and trafficking of drugs (EMCDDA 2019). For this reason, all drugs – including their sale, production, dealing or possession – are illegal in the Netherlands (Government of The Netherlands 2020b).

What makes the country special however, is its practical approach towards the enforcement of these policies: First, the Netherlands recognize that it is impossible to prevent people from using drugs altogether. The Dutch government therefore designed a policy which tolerates the distribution of less harmful soft drugs – namely cannabis products, hallucinogenic mushrooms, sleeping pills and sedatives – under strict terms and conditions. Coffeeshops and smartshops are not allowed to advertise, or provide access to their premises to minors for example. Furthermore, there is a restriction on the maximum amount of drugs these establishments are allowed to sell. For coffeeshops, this upper limit lies at 5 grams of cannabis per person (Government of The Netherlands 2020c). Overall, this more tolerant approach is meant to protect consumers of soft drugs from engaging with criminal dealers who may otherwise easily bring them into contact with hard drugs (Government of The Netherlands 2020b).

A second consideration made by the Dutch government is the importance it assigns to protecting the wellbeing of the individual versus the prosecution of drug users. While the sale, production, dealing and possession of drugs remains illegal, the actual act of taking drugs is not a criminal offense. This is meant to a) encourage users to seek medical attention if the experience goes wrong at any point, and b) free up resources to investigate the organized crime rings providing the general public with narcotics such as heroin, cocaine, MDMA/ecstasy and amphetamines in the first place (Government of The Netherlands 2020a).

Combined, these factors have made the Netherlands a popular destination for international tourists looking to obtain or use drugs for recreational use that are otherwise unavailable, illegal or very expensive in their home jurisdictions (Sleutjes and Bosveld 2019).

Addiction in the Netherlands

Has this institutionalized philosophy of tolerance – despite being targeted at reducing the dangers associated with narcotics – also spilled over into the culture of drug use in the Netherlands? Are citizens of the Netherlands more at risk of drug addiction than other European countries? Here, it is useful to take a closer look at some statistics:

In 2017, cannabis was the most common illicit substance used by the Dutch general population aged 15 to 64, followed at a distance by MDMA/ecstasy and cocaine. The use of both MDMA and cocaine remains particularly widespread among young adults between the ages of 15 to 34. In fact, with prevalence rates of 7.1 and 4.5 percent respectively, the Dutch rank first and second – only behind the UK – in their use of these drugs compared to other EU member states (EMCCDA 2019). Furthermore, available data suggests that the use of cocaine and amphetamine among the general population – especially Amsterdam clubgoers – has increased. Overall however, studies indicate that the use of illicit drugs in the Netherlands is much more common in recreational settings – such as clubs and music festivals – than in everyday contexts (EMCCDA 2019).

High-risk drug use in the Netherlands is mainly linked to heroin and crack cocaine. The most recent estimates from 2012 suggest that there are currently around 14 000 high-risk opioid users – in other words: 1.3 in 1000 inhabitants aged 15 to 64 years – in the country. In the major centers of Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague combined, this number jumps to between 1.6 and 2.2 in 1000 inhabitants. Furthermore, in 2016 a general population survey estimated that 1.4 percent of people above the age of 18 were high-risk cannabis users (EMCCDA 2019).

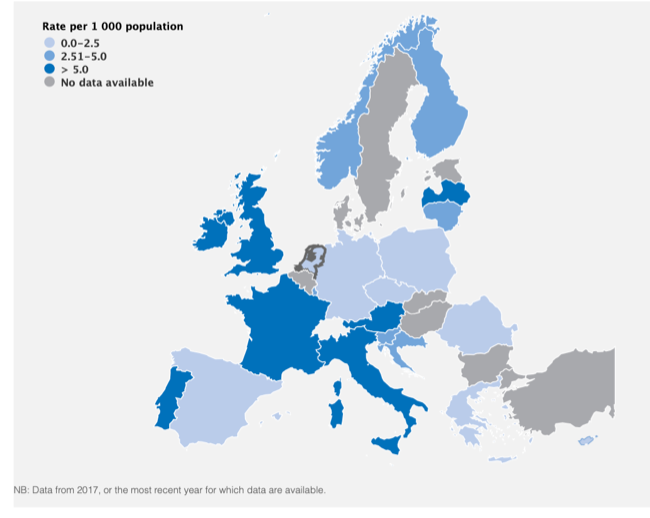

Figure 1. National estimates of prevalence of high-risk opioid use in 2018

Figure 1. National estimates of prevalence of high-risk opioid use in 2018The overall prevalence of high-risk opioid use remains lower in the Netherlands than in other European countries (see Figure 1). While the rates in states such as Italy, France, Austria and the UK exceed 5 per 1000 inhabitants, the Netherlands stays in the lowest category (EMCCDA 2019).

Despite the relatively open-minded attitude of the Dutch population towards drugs then, this does not seem to have translated into a higher risk of addiction. One potential explanation for this apparent paradox could lie in the extensive prevention and harm reduction measures that are promoted by the Dutch government.

Social Protection Efforts in the Netherlands

The Dutch drug use prevention policy is mainly aimed at discouraging drug use and reducing the risks for drug users themselves, for their families and society as a whole. This strategy usually starts at a young age, with universal prevention programs carried out in schools through the Healthy School and Drugs program. This includes education on social norms, self-regulation and impulse control, as well as professional training for educational staff (EMCCDA 2019).

The government has also set up several safety nets that individuals suffering from addiction can fall back on once their drug use begins to spiral out of their control. Examples of services include needle and syringe programs – which provide addicts access to clean needles at little to no cost to prevent the spread of infection –, supervised drug consumption rooms, sheltered living projects, as well as rehabilitation clinics (EMCCDA 2019).

Apart from government-led initiatives, there are also private organizations which try and complement the existing state-led framework of strategies. One organization aimed at harm reduction for example is Drugskompas, located right here in The Hague. Drugskompas offers to test people’s drugs before they take them. This gives consumers a better idea of the exact make-up of the substances they plan on taking, thereby protecting them from taking drugs laced with dangerous and potentially addictive substances. In this way, the organization tries to lower the risk of (accidental) drug dependence even further.

References:

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2019). “Netherlands Country Drug Report 2019.” EMCDDA. At https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/11347/netherlands-cdr-2019.pdf.

Government of the Netherlands (2020a). “Am I committing a criminal offence if I possess, produce or deal in drugs?” Government of the Netherlands. At https://www.government.nl/topics/drugs/am-i-committing-a-criminal-offence-if-i-possess-produce-or-deal-in-drugs.

Government of the Netherlands (2020b). “Difference between hard and soft drugs.” Government of the Netherlands. At https://www.government.nl/topics/drugs/difference-between-hard-and-soft-drugs.

Government of the Netherlands (2020c). “Toleration policy regarding soft drugs and coffeeshops.” Government of the Netherlands. At https://www.government.nl/topics/drugs/toleration-policy-regarding-soft-drugs-and-coffee-shops.

Sleutjes, Bart and Willem Bosveld (2019). “Coffeeshops, prostitutie en toerisme in het Singel/Wallengebied– Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek.” Gemeente Amsterdam. At https://data.amsterdam.nl/publicaties/publicatie/coffeeshops-prositutie-en-toerisme-in-het-singel-wallengebied/190e82f5-27d0-43de-b0bc-b11addad0dcc/.