Author: Struggle in the City Team

A feeling of hunger, a lack of shelter, being sick and unable to see a doctor. Unemployment, a fear of the future, living one day at a time.

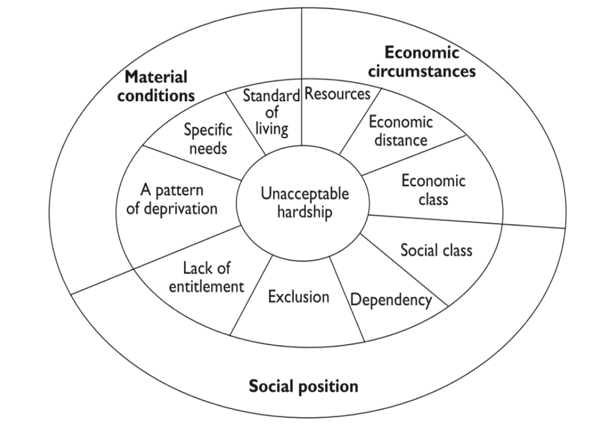

Poverty can wear many faces, changing from place to place and time to time. Some of its conceptualizations are easy to quantify and measure: economic circumstances for example can be measured using household income levels (EAPN 2020). Material conditions are regularly examined by assessing a household’s access to a standardized list of material goods (EAPN 2020). Other conceptualizations – while equally important – are much more difficult to operationalize however. How for example, can we measure something as blurred and context-specific as the social dimension of poverty?

Figure 1. Family resemblances between different concepts of poverty (Spicker 2007)

Figure 1. Family resemblances between different concepts of poverty (Spicker 2007)The Social Dimension of Poverty

Spicker (2007) summarizes the social dimension of poverty as follows (see Figure 1):

1. Poverty as a Social Class:

Here, social class refers to a combination of economic position, level of education and social status. Many connect poverty to the lowest social position, characterized by a lack of status, power and opportunities available to others.

2. Poverty as Dependency:

This definition sees poverty as a dependency on social assistance. Here, anyone who is reliant on social welfare to get by in daily life is considered poor.

3. Poverty as Exclusion:

This term is a bit more confusing, referring to people who are excluded from society. According to this understanding, those who are unable to participate in society in some way, vulnerable people who are not protected properly (e.g. asylum seekers or disabled people), and those who are socially rejected (e.g. drug users or people suffering from AIDS) are considered poor.

4. Poverty as a Lack of Entitlement:

Finally, Amartya Sen argues that poverty is best understood not as a lack of goods but rather as a limitation on one’s capabilities. Capability is understood as an individual’s freedom to have different lifestyles (dos Santos 2017). Thus, poverty describes the complex intersection between legal, social and political arrangements that limit a person’s freedoms and choices to live according to their preferences.

Measuring Poverty in The Hague

In general, there are two extremely useful sources of data for measuring the social dimension of poverty in The Hague: CBS and “Den Haag in Cijfers” (Cijfers) provided by the municipality of The Hague itself. Each source provides indicators for a range of topics, CBS for both national and more local areas, and Cijfers for the municipality of The Hague itself. A particularly valuable feature of the latter are its neighborhood reports: Here, you can zoom in on a district of choice to analyze the environment and the population living in that area.

The following indicators from both CBS and Cijfers are useful for operationalizing the social dimension of poverty:

1. Poverty as a Social Class:

To fully capture this category, we need to draw from several different groups of indicators. Both CBS and Cijfers provide information on a household’s financial situation, level of education, occupation and more. Here, useful indicators might include the average disposable income of private households, school drop-out rates and employment status for example. Furthermore, Cijfers also provides neighborhood reports with a focus on “Armoede” (poverty). In these reports, you can find more information on the financial situation of the inhabitants of each of the neighborhoods of The Hague.

2. Poverty as Dependency:

This is perhaps the most straightforward category to operationalize and measure: Simply check which parts of a population are dependent on welfare assistance and in what way. Again, both CBS and Cijfers offer information on welfare benefits and social assistance. Here, indicators are grouped under “Labor and social security” (CBS) and “Health care and welfare” (CIjfers).

3. Poverty as Exclusion:

This is a broader category than the previous and therefore offers more potential approaches to operationalization and measurement. On the one hand, you might want to look at a population group’s personal profile: How many asylum seekers are there in a specific area? How many people suffering from mental illness? What are people’s opinions towards these groups? In this regard, Cijfers is particularly useful: Not only does it provide various types of demographic information (see e.g. indicators grouped under “health care and welfare”), it also offers information on citizens’ perceptions of their neighborhoods. Here, indicators such as “Voelt u zich thuis in Den Haag” (Do you feel at home in The Hague?) are an interesting way to gauge social exclusion.

Apart from a person’s background, you can also use statistics to examine their participation in economic and social activities. Here, CBS offers a starting point: The organization regularly compiles information on topics such as “membership in associations,” “social contacts” and “internet use of persons.”

4. Poverty as a Lack of Entitlement:

In order to be able to measure a lack of entitlement or capabilities, one must first decide what those basic capabilities are. While there is no agreed-upon set of basic capabilities, academics such as Martha Nussbaum (2007) argue that these should include being able to live a life of normal length, having good health and bodily integrity, the capacity for senses, imagination and thought, having control over one’s environment and being able to enjoy recreational activities. Based on these capabilities (and more), there are several indicators we might use to measure a lack of entitlement: Crime rates (Cijfers), air quality (Cijfers), cultural supply (Cijfers), rate of informal care (Cijfers), school drop-out rates (Cijfers), legal protection (CBS), domestic violence key figures (CBS) and health and wellbeing (CBS) are only the start. Take a look around and you are sure to find an abundance of data for The Hague.

Ultimately, how you decide to measure the social dimension of poverty will always depend on your definition. But perhaps these indicators can represent a starting point.

References:

dos Santos, T. M. (2017). “Poverty as Lack of Capabilities: An Analysis of the Definition of Poverty of Amartya Sen.” PERI 9(2): 125-148.

EAPN (2020). “How is poverty measured?” European Anti-Poverty Network. At https://www.eapn.eu/what-is-poverty/how-is-poverty-measured/.

Nussbaum, M. (2007). “Human Rights and Human Capabilities.” Harvard Human Rights Journal 20: 21.

Spicker, P. (2007). The Idea of Poverty, Bristol: Policy Press.