Author: Lindah Muturi

Home should represent solace; a place where we look forward to coming back to at the end of the day. A place where we can be ourselves, regardless of the people around us.

For victims of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) who are living with their abusers however, the security normally associated with having a place to live is stripped away. It takes incredible strength and courage for victims to leave their significant others. When they decide to do so, the interrelated nature of relationships makes it difficult for the victims to remove themselves. A key hurdle that these victims have to navigate through is how they can move out without putting themselves, and their children, in harm’s way when their abuser realizes that they want to leave.

The Hague’s Home Ban

In an effort to give the abused partners the confidence to sound the alarm and the time to pack and leave their homes, the Netherlands adopted a House Ban (huisverbod) in 2009.

The House Ban refers to a 10-day period where the police issue the perpetrator a Temporary Restraining Order which prohibits them from coming back to their house or communicating with their partner or other threatened family members in the period (Public Result). The ban holds even if the perpetrator owns the house the victim is living in (Den Haag 2015). During this period, the victim is expected to work with social workers to find ways to remove themselves from the situation or resolve the situation with their partner. Some victims take the time to reach out to relatives and friends in an effort to find alternative housing, while victims with children work with the social worker to plan out whether they want their children to have a relationship with the abusive partner. If the victim is not able to make a clear plan within the 10 days, the time period may be extended to 28 days (Public Result 2009).

Is it helping?

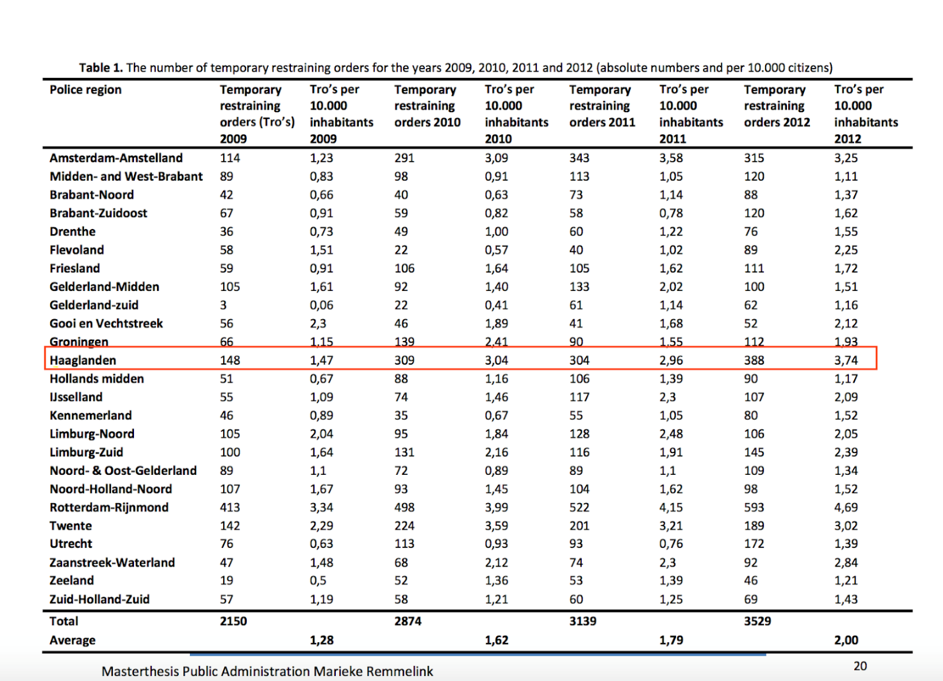

In the three years following the introduction of the ban, the amount of cases of women filing the Temporary Restraining Order (TRO) against their partners have been increasing in The Hague. A report circulated by the Municipality of the Hague shows that by 2012 the Haaglanden region (The Hague) had the second highest absolute number (388 citizens) of TROs and of TROs per 10,000 inhabitants (3.74) (Remmelink 2013). The high number of TROs per 10,000 shows that the region cannot just chalk the high number of absolute TROs to its large population. Although the reason for the increase and the high number of TROs is not clearly explained, the data highlights that there is a high number of women in The Hague who feel unsafe with their partners.

Source: Remmelink 2013

Source: Remmelink 2013

However, even with the Home Ban in place, about 20% of the affected households will experience a repeat of IPV (NOS 2018). In an effort to increase the agency that women facing IPV feel that they have to come out of their situations, the former mayor of the Hague, Pauline Krikke, pushed to lower the threshold at which IPV victims could seek help (NOS 2018). Krikke took a more preventative approach to protecting women who are facing IPV at home. Currently, only women who exhibit proof that they are being abused can seek a Home Ban (Huiselijkgeweld.nl 2018). This results in many women not being able to sound the alarm because their situations have not escalated ‘enough’ to warrant help from the police.

The numbers following the implementation of the House Ban in 2009 have proven that there remains a need to aid victims of IPV in The Hague to leave their abusive partners. While the implementation of the Home Ban still needs to be ironed out, Krikke’s project shows that the municipality is invested in ensuring a safe living environment for the victims of IPV and their children.

References:

Den Haag (2015). “Tijdelijk Huisverbod.” Den Haag. At https://www.denhaag.nl/nl/in-de-stad/veiligheid/tijdelijk-huisverbod.htm.

Huiselijkgeweld.nl (2018). “Doorbraakteam Moet Aanpak Huiselijk Geweld in Den Haag Verbeteren – Huiselijk Geweld.” Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport. At www.huiselijkgeweld.nl/nieuws/2018/130218_doorbraakteam-moet-aanpak-huiselijk-geweld-in-den-haag-verbeteren.

NOS (2018). “Burgemeester Den Haag wil vaker huisverbod bij huiselijk geweld.“ NOS. At https://nos.nl/artikel/2216878-burgemeester-den-haag-wil-vaker-huisverbod-bij-huiselijk-geweld.html#:~:text=Burgemeester%20Pauline%20Krikke%20van%20Den%20Haag%20wil%20dat%20er%20vaker,aan%20plegers%20van%20huiselijk%20geweld.&text=Volgens%20de%20burgemeester%20is%20zo,het%20vaker%20moeten%20worden%20ingezet.

Public Result (2009). “Implementatie Huisverbod Den Haag.” Public Result. At www.publicresult.nl/project/coordinatie-en-implementatie-huisverbod-gemeente-den-haag/.

Remmelink, M. (2013). “The use of a temporary restraining order in the Netherlands A study of regional differences in the use of the temporary restraining order between 2009-2012.” Master’s Thesis, University of Twente. At http://essay.utwente.nl/64448/.